Why we need C++ Exceptions

There are modern programming languages which don’t (or won’t) support exceptions (e.g. Rust, Carbon). We’ve used C++ exceptions for our UML Editor. I believe it would have been difficult to implement our editor without exceptions.

We have task objects which create transaction objects. Task objects handle events from Windows. We do have a single place where we catch exceptions and undo unfinished transactions. Finished transactions produce an undoer object. The undoer is kept in a list in memory. We support “unlimited” undo. Catastrophic exceptions like stack overflow are handled at the top level. The model objects all call member functions of other model objects.

For example, in class diagrams, we have class objects, association segments, joins and ends. If the user moves a class object, the attached assoc end moves together with the class. The class object calls into a member function of assoc end to move it. So the size of the call stack depends on the data structure of the objects. Edits by users may result in call chains that never end if we have an error in our generic connector movement code. We didn’t want that the users lose an unsaved diagram if we have an error in our software that leads to never ending call loops. If a stack overflow happens during a transaction, an exception is thrown1 and catched and the unfinished transaction is aborted, which restores all touched objects into the state they had before the transaction. The transaction knows all touched, newly created and deleted objects.

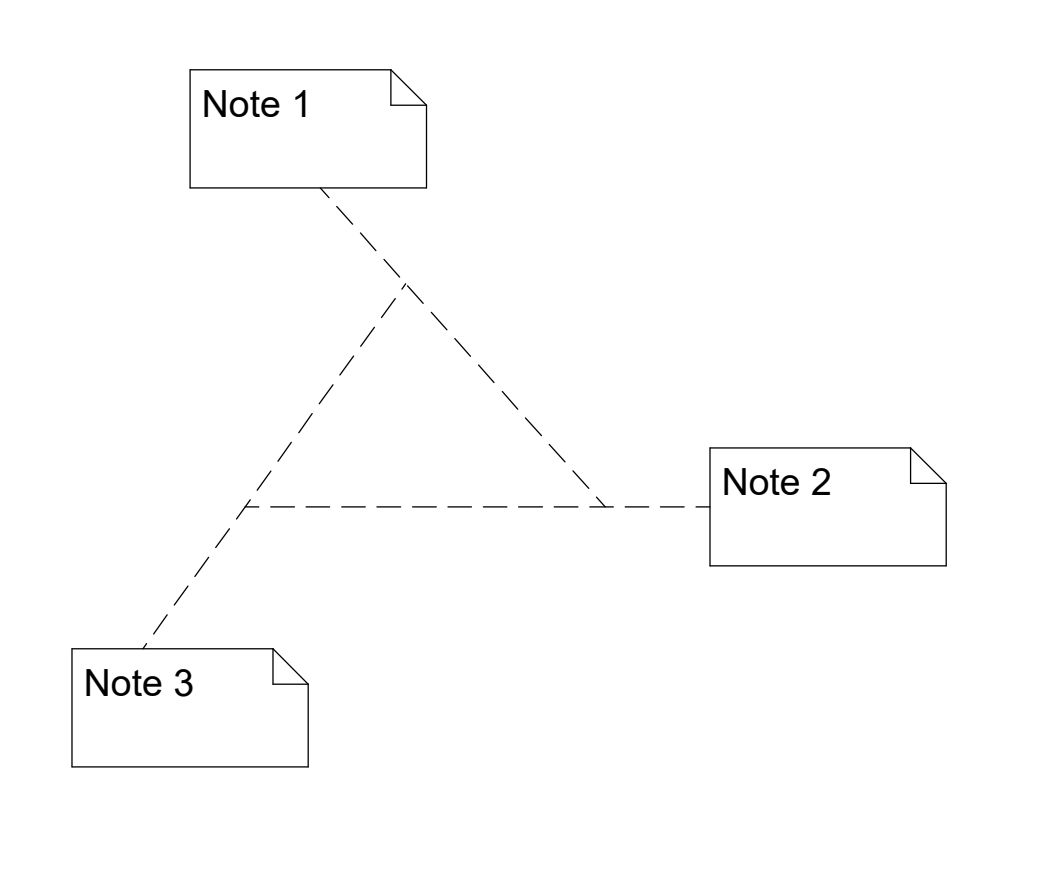

We once found a blocking bug in our software during internal testing. The bug was triggered by a pathological diagram, which consists of three UML notes, which are connected to each other’s connectors. For fun, we called it the borg virus. It is really difficult to think in advance of all the weird cases.

A scond place where exceptions were really useful is our XML package, which deals with writing and reading diagram files. Diagrams are stored in XML format. The serialization of the model elements is spread throughout the whole software. Basically, model elements know how to restore themselves from persistent data. That code knows nothing about the details of parsing an XML file. Tunneling XML parsing errors through the restoration layer of model elements would have been a massive pain, if we would have been forced to do the error reporting with return values of function calls. Instead, the XML parser throws an exception, if a file has an error in the XML structure. The error is catched at a high level in our software and the user gets an error window, if a file can’t be parsed. The read operation is then aborted.

Furthermore, it’s nice that the old, perennial code bloat myth about C++ exceptions now got busted: See the ACCU 2025 talk “C++ Exceptions are Code Compression” by Khalil Estell. However, even though we used C++ Exceptions and RTTI, our binary is ridiculously small for a Windows application anyway (~3 MB).

Our editor supports Windows drag and drop. So we had to deal with the full complexity of Windows, which includes all COM horrors. We didn’t use any library. Just the C++ standard library and the Windows API. The editor looks like it was easy to develop, but it is a quite complex piece of software. All done in C++. At the moment in C++ 23. Which includes modules. The editor was started before C++11. We used C++ exceptions from the beginning. Imagine our pleasure when we could start using std::unique_ptr, shared_ptr and auto. Recently, I’ve converted our code base to use C++ modules.

(last edited 2025-09-11)

-

We have used Windows SEH and _resetstkoflw. We translate SEH exceptions into C++ exceptions. ↩